By Ryan Hamnett, PhD

Immunoprecipitation (IP) is a technique for enriching or purifying a target protein from a complex mixture using specific antibodies that are immobilized on a solid bead support. Proteins isolated by IP can be further investigated by ELISA, western blot (WB), mass spectrometry (MS) and functional assessments to understand the presence, relative abundance, stability and post-translational modifications of the target antigen.

This guide aims to provide an overview of IP formats, experimental design, important controls, protocols, and troubleshooting. The critical technical aspects of IPs will be discussed, providing an approach that can then be tailored to your specific research objectives.

Using antibodies to precipitate target proteins has its origins in the 1960s, when Barrett et al. referred to immunoprecipitation as a tool for measuring the concentration of gamma globulins in human serum, offering more precision than other techniques available at the time such as electrophoresis.1,2 It was further developed as an alternative to traditional column affinity chromatography, in which samples are passed across a column of resin, typically agarose, onto which an antibody has been immobilized in order to capture the target antigen. IP uses the same principle but in a scaled-down, batch-wise format, whereby individual tubes contain the agarose resin, making it a convenient way to purify protein from multiple small samples. The discovery and application of Protein A3 and Protein G4 as a way of consistently immobilizing any capture antibody to the solid support improved the efficiency and versatility of IPs. Further advances in beads, such as magnetic beads, have enhanced reproducibility and capacity for automation, while integration with other techniques such as WB and MS continue to expand its utility.

IPs are not limited to a single protein target, with expansions to the original IP format enhancing its versatility and enabling the study of protein-protein (Co-IP), protein-DNA (ChIP) and protein-RNA (RIP) interactions.

Individual Protein Immunoprecipitation (IP)

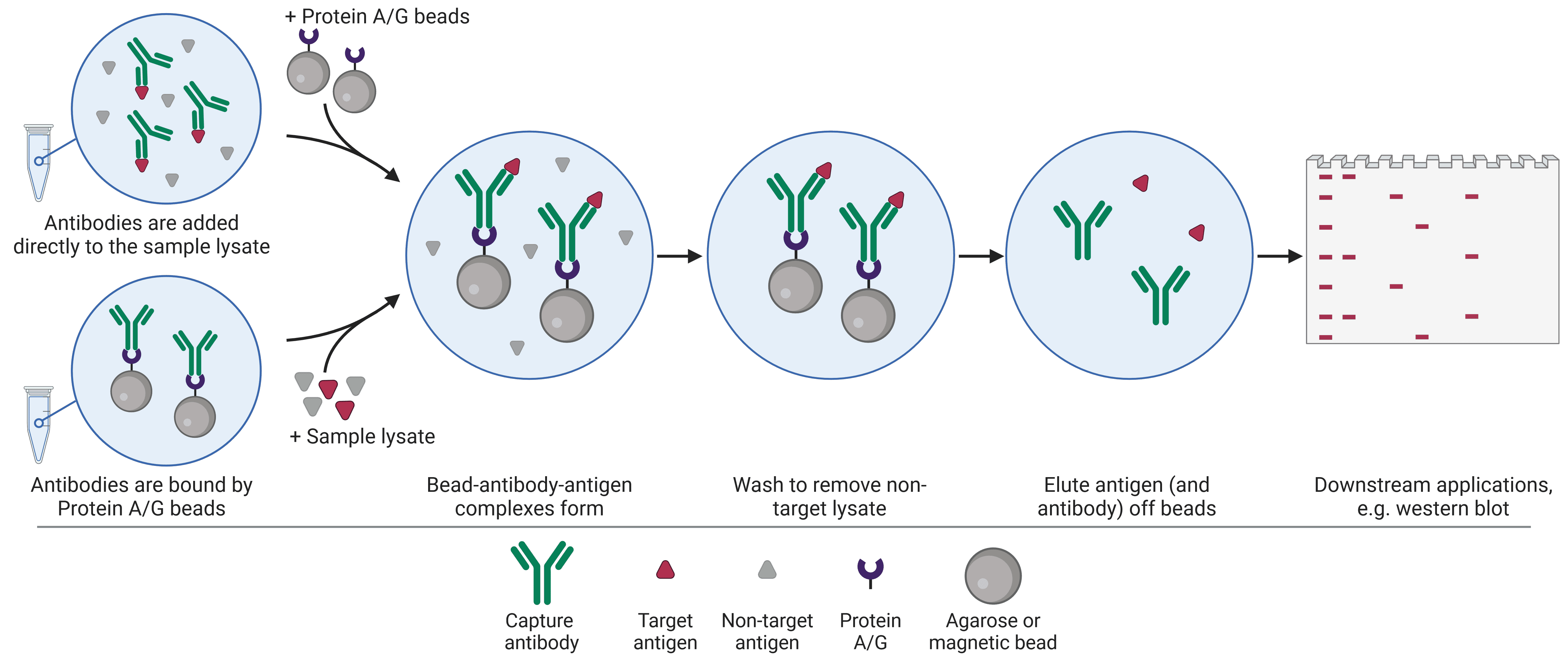

IP is conventionally used to isolate a single protein of interest from a heterogeneous mixture. There are two standard approaches when performing an IP (Figure 1). In the pre-immobilized antibody method, also known as the direct method, an antibody specific for the target antigen is first immobilized onto a bead support. Once immobilized, the bead-antibody complex is added to the sample in order to capture the antigen. In the free antibody, or indirect, method, the antibody is added to the sample first, allowing antigen-antibody complexes to form. Then the beads are added to capture the immune complex.

Figure 1: Schematic of individual protein immunoprecipitation (IP) workflow. IP can be performed in one of two ways, in which the antibody is first added to the lysate to capture the target before the beads are introduced, or the antibody is first immobilized to the beads.

Regardless of which approach is taken, the sample is then centrifuged in order to collect the beads, which are bound to the antibody and antigen, in a pellet at the bottom of the tube, thus precipitating out the target antigen. This pellet is washed and re-pelleted several times to remove as much non-specifically bound material as possible. The target antigen is then eluted, dissociating the antigen (and often the capture antibody) from the bead, ready to be used for downstream application such as sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and WB.

Protein Complex Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

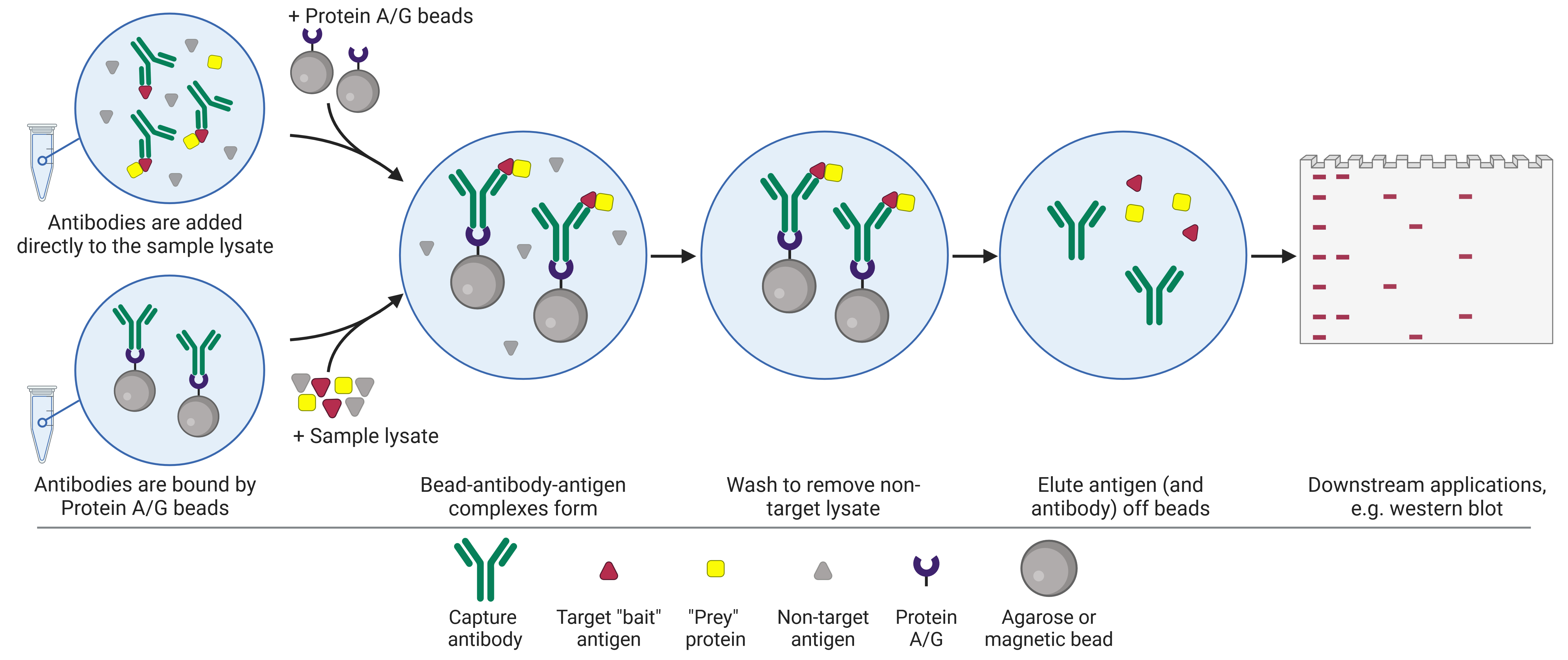

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) follows a similar workflow to the individual IP (Figure 2), but instead of purifying a single known protein (the “bait”), the aim is to co-precipitate unknown proteins (the “prey”) that are bound to the target antigen, on the basis that binding partners are likely related to, and may be required for, the function of the antigen. These prey proteins may include activators or inhibitors, kinases and other mediators of post-translational modifications (PTMs), ligands, and so on. Thus, protein complexes are precipitated and can be studied in similar ways to IP products, facilitating protein-protein interaction discovery.

A full description of the factors involved in performing co-IP can be found in our Co-IP Guide.

Figure 2: Schematic of co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) workflow.

Pull-down Assay

Pull-downs involve precipitating protein complexes based on protein-protein interactions captured on a solid bead substrate, and are therefore very similar conceptually to co-IPs. However, pull-downs do not use antibodies and are therefore not a type of immunoassay. Instead, the bait protein itself is immobilized to a bead without the antibody bridge.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

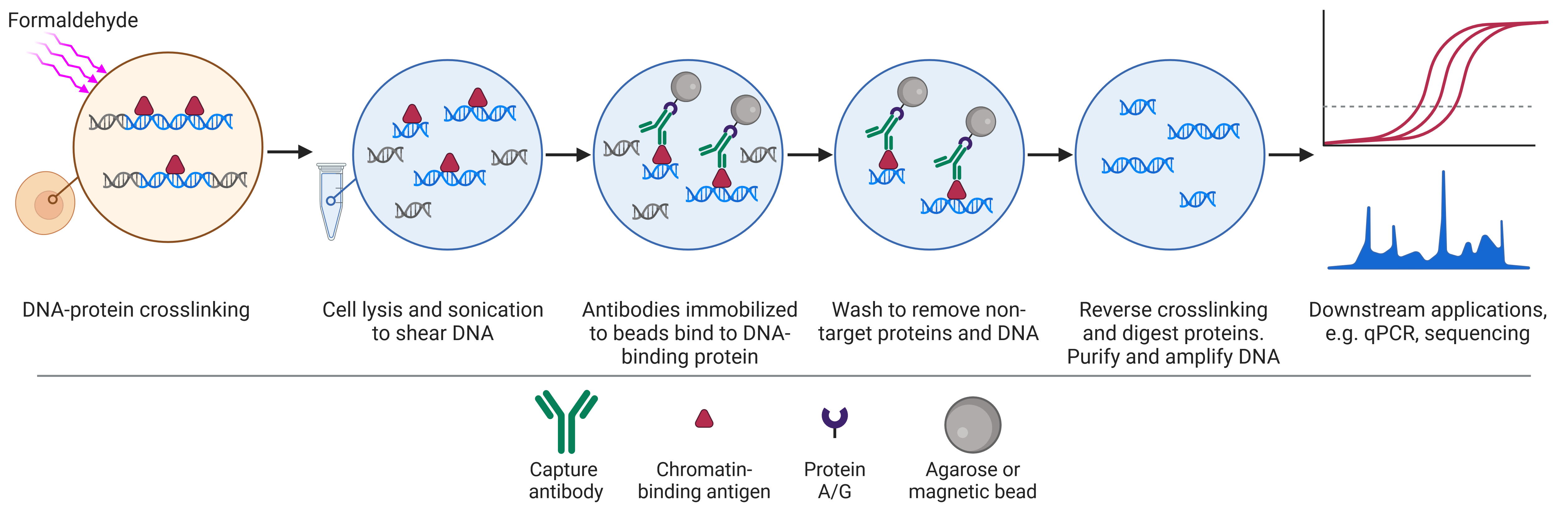

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is a format of immunoprecipitation used to investigate protein interactions with DNA (Figure 3), typically with the aim of identifying regions of the genome associated with a specific DNA-binding protein, such as transcription factors and histones.

The workflow of ChIP differs slightly from that of IP and co-IP because it begins by cross-linking proteins to DNA, usually by formaldehyde treatment, preserving the state of the cell (for example, after a certain treatment). Cells are then lysed and sonicated to shear DNA, resulting in small pieces of DNA attached to DNA-binding proteins. The proteins can then be captured as in regular IP, using specific antibodies immobilized on beads. Following dissociation of the DNA from the protein, the DNA is analyzed by PCR, microarray or sequencing.

Figure 3: Schematic of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) workflow.

ChIP offers advantages over other techniques for investigating protein-DNA interactions by virtue of reflecting the native, intracellular context of protein-bound DNA, as opposed to in vitro assays such as the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), and can therefore account for the effects of epigenetics as well as known and unknown binding partners.

A full description of the factors involved in performing ChIP can be found in our ChIP Guide.

RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

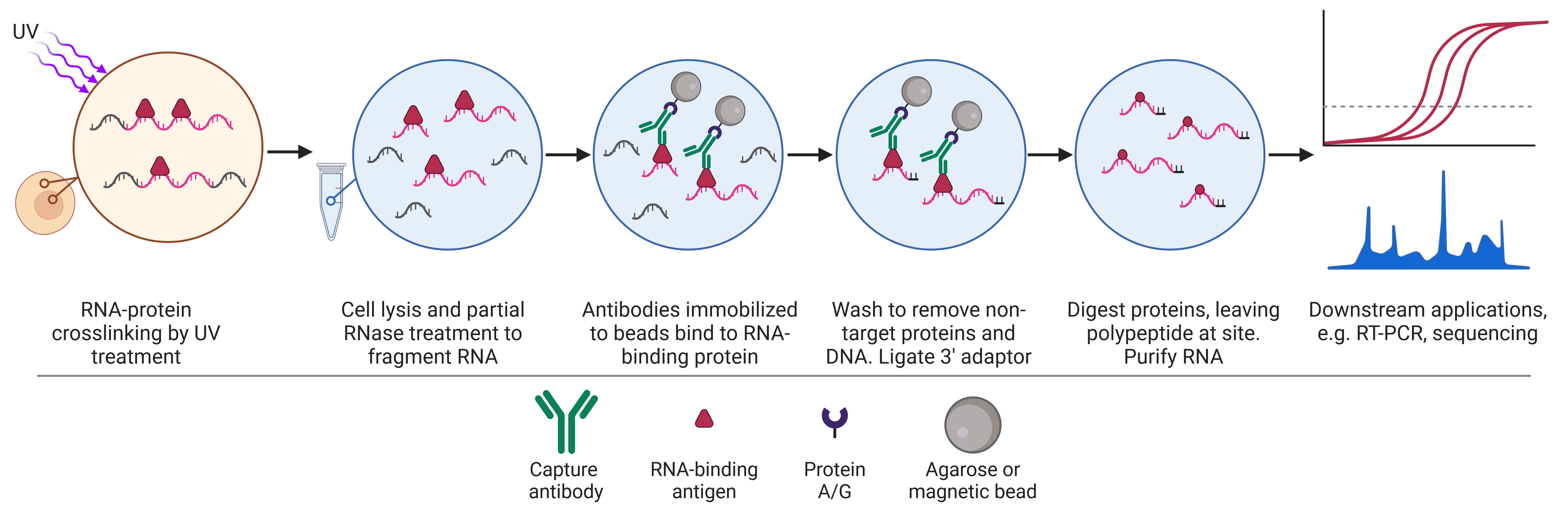

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) is similar to ChIP, but uses an antibody targeting RNA-binding proteins (RBP) of interest, which modulate the function of mRNA or noncoding RNA in ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNP).

There are two main types of RIP, referred to as native RIP and cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP).5 Native RIP allows the identification and abundance of RNAs bound to the RBP of interest, but it misses more transient RBP-RNA interactions and can suffer from low specificity and low reproducibility due to non-stringent conditions.6 CLIP, derived from RIP,7 increases specificity, allows recovery of weaker protein-RNA interactions, and allows higher resolution mapping (e.g. single nucleotide resolution)8,9 of the precise RNA binding sequence due to stringent purification conditions enabled by the UV cross-linking. UV cross-linking is advantageous when targeting RBPs because UV crosslinks are irreversible, do not form between proteins,10 and only form between proteins and RNAs that are in very close proximity. CLIP has become the standard technique to assess RNA-protein interactions at genome-wide scale, though further advancements to address its limitations continue to be developed.11,12

The workflow for native RIP begins with cell lysis, while CLIP begins with UV cross-linking prior to lysis (Figure 4). Partial RNase digestion in both approaches results in short RNA fragments bound to RBPs, which are immunoprecipitated as described for the other formats, using specific antibodies immobilized on beads to capture the RBP-RNA complexes. 3’ adaptor ligation is then performed to enable amplification downstream. Further purification via denaturing gel electrophoresis and transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane may be employed here, particularly in CLIP, allowing excision of the protein-RNA complexes while removing lone protein and nonspecific RNAs.9,12,13 The sample is then subjected to proteases that will degrade the RBP and release the RNA for analysis by RT-PCR, hybridization, or sequencing.

Figure 4: Schematic of crosslinking and RNA immunoprecipitation (CLIP) workflow.

| IP | Co-IP | ChIP | RIP/CLIP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Known protein | Protein complexes | DNA-binding proteins (histones, transcription factors) | RNA-binding proteins |

| Purpose | Purifying or enriching a single protein | Protein-protein interactions | Protein-DNA interactions | Protein-RNA interactions |

| Applications | Small scale enrichment or purification of proteins for downstream biochemical, biophysical or structural analyses Investigate PTMs Enrichment for WB analysis Epitope mapping Removal of a protein from a lysate | Discover new protein-protein interactions Prove interaction between bait and hypothesized prey Map protein interaction networks Understand dynamic protein interactions in different conditions | Understand how DNA-protein interactions change with time, treatment or cell state Identify DNA regions of high or low expression based on histone modifications Inferring the function of an unknown histone modification Identify genetic elements such as enhancers via histone modifications | Understand how RNA-protein interactions change with time, treatment or cell state Understand subcellular localization of RNA-RBP interactions Study how specific RBPs mediate RNA modifications |

| Limitations | Potential for high background due to non-specific interactions with bead, Protein A/G or antibody Antibody will be eluted alongside target protein unless covalently immobilized | Hard to capture transient interactions Indirect protein interactions may confound results Capture antibody for bait protein may interfere with bait-prey interaction Interactions must be verified by other methods Typically only qualitative | Complex, requiring optimization of many steps Can yield low signal Requires relatively large numbers of cells Resolution is limited to the size of DNA fragment May not capture transient DNA-protein interactions Protein binding partners may mask epitope | Complex, requiring optimization of many steps RIP does not identify precise binding site RIP has low specificity and reproducibility, misses transient interactions (note that these are largely solved by CLIP) CLIP may crosslink non-specific interactions |

| Variations and extensions | Pull-down | ChIP-chip; ChIP-seq; ChIP-exo; ChIA-PET; enChIP; iChIP | RIP-chip; RIP-seq; HITS-CLIP; PAR-CLIP |

Table 1:Key applications and differences between IP formats.

IP with Tagged Proteins

IPs rely on the highly specific binding of an antibody to an antigen. In the absence of an antibody that exhibits strong specificity towards a protein of interest, one solution is to instead ‘tag’ the protein of interest with a peptide sequence or fluorescent protein for which a high affinity antibody is available. Tagging, which involves placing the DNA sequence for the tag at either the C- or N-terminal of the target protein sequence, can be achieved via genetic modification in model organisms, or expression of a recombinant protein from a plasmid or viral vector. The disadvantage of protein tagging is that the tags themselves may affect molecular interactions. Nevertheless, it has become a standard method for protein purification.

Common peptide sequences are listed below:

IP is an ideal technique for the small-scale enrichment or purification of proteins, as an alternative, batch-wise method to column affinity chromatography. Once the target protein has been eluted, it can be assessed by any biochemical, biophysical or structural technique, but a common next step is to analyze it using SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the gel can be stained with Coomassie blue or silver stain to visualize the protein and confirm its purity and molecular weight. More commonly, the protein will be transferred to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane and visualized by WB.

Running a WB on an immunoprecipitated protein offers advantages over performing the WB against the original cell lysate. Primarily, the resultant enrichment of the antigen makes it possible to detect low abundance proteins that otherwise may not have been detectable by WB.

This is particularly valuable when investigating specific PTMs on a target protein, which will be lower abundance than all forms of the protein. Thus, many studies of PTMs begin with IP, though it is important to remember that PTM modifications may block the binding site of the IP antibody. In this instance, a PTM-specific antibody can be used, followed by WB probing for the protein of interest. This offers significant flexibility, with kits often available containing PTM-specific antibodies pre-conjugated to beads, and can bypass issues arising from lacking a target protein-specific antibody validated for IP conditions.

In other cases, MS can be used. The efficiency of PTM detection can be low without prior enrichment (e.g. by IP) for mass spectrometric analysis of PTMs;14 following IP, eluted proteins can be subjected to MS immediately, or can be extracted from an excised portion of a stained SDS-PAGE gel or WB membrane. MS does not rely on antibodies and can be less biased than WB, though it is far more expensive and requires specialized equipment.

IP begins with separating soluble proteins from a lysate, typically from cells or tissue. Tissue usually needs to be homogenized in order to make cells fully accessible to the lysis buffer, while lysis buffer can be directly added to cell culture after washing. Brief sonication of samples can sometimes help to disrupt the nuclear membrane to release nuclear proteins, but often agitation of cells or tissue homogenate in lysis buffer for 30 minutes on ice is sufficient to release soluble proteins. Insoluble material can then be pelleted, while the supernatant will be taken forward for IP.

The amount of total protein needed for successful IP will depend on the abundance of the protein and the affinity of the antibody. For a cell culture lysate, approximately 300 µg of total protein is a useful starting point. This can be increased up to 2 mg for low abundance proteins, but more starting material may increase background. If the target protein is only present in one region of the cell, such as the nucleus, a more refined option is to perform subcellular fractionation first in order to increase the abundance of the target as a proportion of the total input pool.

Something that is essential to do in any IP protocol is to set aside 1-10% of the lysate (before the addition of any antibody, beads etc.). This is termed the input, and represents the starting sample material. The input will be run alongside the precipitate at the end of the experiment (e.g. by WB). This is a useful positive control to determine if the IP has worked: if a band is seen in the input but not the IP, then the IP did not successfully precipitate the protein. The input is also a useful control to give a sense of 1) efficiency, by comparing the strength of the target band in the IP lane to the band in the input lane, and 2) specificity, by comparing the strength of consistent non-specific bands between the lanes. Finally, it serves as quality control to ensure that the starting material is consistent across different experiments or samples.

Lysis Buffers

One of the most important technical aspects of IP is the lysis buffer, the choice of which will depend on the sample type and purpose of the experiment. Lysis buffers should stabilize native protein conformation, inhibit enzyme activity to decrease degradation and PTM modification, and rupture membranes for protein release from cells. The location of the protein in a cell (e.g. in the cytosol, nucleus) can affect how easily a protein will be released, which in turn will affect the choice of lysis buffer.

The most important lysis buffer consideration is whether the buffer used contains ionic or non-ionic detergent. Ionic detergents contain a charged head group and have a much stronger denaturing effect, which can result in altered protein conformations and protein-protein interactions. Non-ionic detergents are non-denaturing and less harsh than ionic detergents, meaning they are less likely to affect protein-protein interactions. Given that co-IP relies on protein-protein interactions, ionic detergents generally cannot be used. RIPA (radio-immunoprecipitation assay) buffer is commonly used in WBs and sometimes recommended for IP, but it contains sodium deoxycholate and SDS (0.01-0.5%), which are ionic and will disrupt protein-protein interactions. Nevertheless, ionic, denaturing lysis buffers can still be useful for individual protein IP as some proteins can be difficult to release with only non-denaturing buffers, or an antibody may only recognize a denatured protein form. Buffers containing NP40 or Triton X-100 (0.1-2%) are useful, non-ionic alternatives to RIPA, but may result in slightly higher background. Buffers that completely lack detergent are also available for proteins that can be released using only physical disruption, usually consisting of just EDTA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

Both ionic and non-ionic lysis buffers tend to contain NaCl and Tris-HCl, and usually have a slightly basic pH (7.4 to 8), though this can be optimized (between pH 6-9). Other buffer components that can be optimized include: salts (0-1 M) for maintaining ionic strength and correct tonicity for easy cell lysis; divalent cations such as Mg2+ (0-10 mM) which can help to prevent DNA causing the solution to become viscous; and EDTA (0-5 mM) for chelating ions such as Zn2+ that proteases require for proteolytic function.

Enzyme Inhibitors

The final components of lysis buffers are inhibitors of proteases and enzymes that alter protein PTMs, particularly phosphatases. Protease inhibitors prevent the degradation of target proteins, while PTMs are often necessary for protein-protein interactions and so must be maintained for co-IP. Preserving PTMs is obviously essential if the target of the IP is to understand the PTM state of target proteins.

Inhibitors should be added fresh, immediately before lysis buffer use. Table 2 and Table 3 contain common inhibitors used in lysis buffers.

| Protease inhibitor | Typical concentration | Solvent | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aprotonin | 1-10 µg/ml | Water | Serine proteases: trypsin, chymotrypsin, kallikrein, plasmin |

| Benzamidine | 15 µg/ml | Water | Serine proteases: trypsin, plasmin, thrombin, factor Xa |

| EDTA/EGTA | 1-10 mM | Water | Metallo proteases |

| Leupeptin | 1-2 µg/ml | Water | Serine and cysteine proteases: plasmin, trypsin, papain, cathepsin B, thrombin, calpain |

| PMSF | 0.1-1 mM | Methnaol | Serine and cysteine proteases: trypsin, chymotrypsin, thrombin, papain |

| Pepstatin A | 1-3.5 µg/ml | Methanol | Aspartic acid proteases: pepsin, cathepsin D, renin, chymosin, HIV- and MMTV-proteases |

Table 2: Commonly used protease inhibitors in IP. Note that protease inhibitor cocktails are commercially available (often as tablets) and provide a convenient way to ensure protease inhibition.

| Phosphatase inhibitor | Typical concentration | Solvent | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Glycerophosphate | 1 mM | Water | Serine and threonine phosphatases |

| Okadaic acid | 10-1000 nM | DMSO or ethanol | Protein phosphatase 1/2a |

| Sodium fluoride | 10 mM | Water | Serine and threonine phosphatases |

| Sodium orthovandate | 1 mM | Water | Tyrosine phosphatases |

Table 3: Commonly used phosphatase Inhibitors in IP. Phosphatase inhibitor cocktails are commercially available (often as tablets) and provide a convenient way to ensure phosphatase inhibition. Note that while phosphatase inhibitors are typically included in IP buffers, inhibitors of other PTMs, such as ubiquitination and methylation, are included only as needed, determined by the aims of the experiment.

Pre-clearing is an optional but often worthwhile step to reduce non-specific binding in IP. Pre-clearing refers to incubating samples with the beads (including Protein A/G or other attachment substrates), or with a nonspecific antibody from the same host species as the IP antibody immobilized to the beads, in order to remove lysate components that bind to beads or immunoglobulins non-specifically. This prevents these components from being carried through and ultimately eluted, therefore resulting in a purer final product containing predominantly the target antigen.

Reducing non-specific binding can also be achieved by pre-blocking the bead. This works in a similar way to blocking in immunostaining, western blotting and ELISA. The bead is incubated with a mild blocking buffer containing 1-5% BSA, non-fat milk, 1% gelatin or 0.1-1% Tween-20 to block sites of non-specific binding on the bead, preventing lysate components from binding.

Pre-clearing is not necessary if the target is particularly abundant, and is less important if using magnetic beads over agarose beads, because magnetic beads are less prone to non-specific binding.

The supernatant from a pre-clearing step can be kept for WB analysis to confirm that no target antigen was removed during the pre-clearing step.

Antibodies are generated by the immune system of a host organism (e.g. mouse, rabbit) that has been repeatedly immunized with a specific antigen. The antibodies recognize and specifically bind to that antigen with a high affinity, allowing the protein to be precipitated from the lysate. High specificity is essential for a successful IP, as non-specific binding can result in high background or false positive results.

To confirm the specificity of the antibody-antigen interaction, an isotype control should be included. The isotype control consists of a non-immune antibody of the same isotype as the experimental antibody. This should not have any affinity for the target antigen, but it may non-specifically bind to other factors, therefore confirming that the precipitated protein band in a WB is specifically recognized by the chosen antibody. Any bands in both the IP and isotype lanes in WB analysis is likely to represent a protein that binds immunoglobulins non-specifically.

The following factors should be taken into account when selecting an antibody.

Reactivity

Primary antibodies will recognize antigens only from certain species, which will be the species that the immunizing antigen was originally from, as well as closely related species. For example, an antibody that recognizes a mouse protein target will often also recognize the same protein in rat, but possibly not in fish. The key determinant of this is how similar the epitope sequence is between species, allowing researchers to predict if an available antibody will work in a non-validated species.

Clonality

Both monoclonal and polyclonal primary antibodies can be used to detect the protein of interest in IPs. Monoclonal antibodies correspond to a single epitope for a given antigen, whereas polyclonal antibodies may recognize multiple epitopes. As a result, polyclonal antibodies are often preferred to monoclonals for IP because they offer a high chance of capturing the target.

Clonality can also be a factor when considering analysis (see also the Analysis section). Using two different antibodies for the precipitation and WB stages can be advantageous to ensure high specificity, using one polyclonal and one monoclonal. A polyclonal antibody for IP gives the highest capture efficiency, while a monoclonal antibody in the WB gives the highest detection specificity.

Application Compatibility

IPs usually seek to isolate proteins in their native conformation, so a chosen antibody should recognize this form rather than denatured protein (as is common in western blotting). This is particularly important for co-IP, ChIP and RIP, in which proper protein conformation is essential for maintaining molecular interactions. In contrast, IPs can be performed on denatured samples, such as if using RIPA buffer or another buffer containing ionic detergents for lysis. If an IP-validated antibody is not available, it is usually acceptable to use one that has been validated for IHC or ELISA, which also work with native proteins.

The type of beads chosen when performing IP is an important consideration and will dictate certain aspects of the overall protocol. Beads are usually either agarose (or Sepharose, which is a tradename for a crosslinked, beaded-form of agarose) or magnetic beads. Table 4 summarizes the key differences between agarose and magnetic beads, which are described further below.

| Agarose | Magnetic | |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 50-150 μm | 1-4 μm |

| Uniformity | Low | High |

| Binding capacity | High | Medium |

| Diffusion | Slow | Fast |

| Washing | Extensive washing Easier to pick up some of the pellet when removing supernatant | Washing steps reduced Less chance of proteolytic damage |

| Yield | Medium | High |

| Time required | 60-90 minutes | 30-60 minutes |

| Automation | No | Yes |

| Reproducibility | Medium | High |

Table 4: Key features of agarose and magnetic beads in IP.

Agarose Beads

Agarose beads tend to be 50-150 μm in size, and they have a very high binding capacity because they are porous, creating a very high surface area per bead that is available for binding to antibodies. However, this can create a requirement to use a large amount of antibody to ensure that every surface of the agarose beads is covered in antibody, lest any unoccupied agarose non-specifically bind to lysate components and increase background signal. To solve this issue, it is possible to back-calculate from the amount of expected analyte to the amount of antibody needed for detection, to the amount of agarose needed to hold the antibody. The downside is that this approach requires significant knowledge or prior experience to estimate such quantities. An alternative would be to simply saturate the beads with excess antibody, but antibody is typically expensive and limiting. The best option is therefore to pre-clear the lysate to remove anything that will non-specifically bind to the agarose.

Magnetic Beads

Magnetic beads lack the porosity of agarose because they are solid spheres, resulting in only the external surface being available for binding. While this may at first glance suggest that magnetic beads have much lower binding capacity, they are much smaller than agarose particles at 1-4 μm, meaning that there can be far more beads per unit volume, so the ultimate binding capacities of the two are similar, with agarose maintaining a small advantage.

Magnetic beads offer several other advantages over agarose for use in IP, however. They are highly uniform in size and have a consistent binding capacity, which can make experiments more consistent between runs. Magnetic beads are manipulated using powerful magnets that pull the beads to one side of a tube so that the supernatant can be removed, obviating the need for centrifugation. Centrifugation can be stressful for protein complexes and can lead to a loss of yield compared to the gentler magnet-based washing steps, thus final yield can be higher with magnetic beads. Magnet-based manipulation is faster and makes IPs more amenable to higher throughput applications.

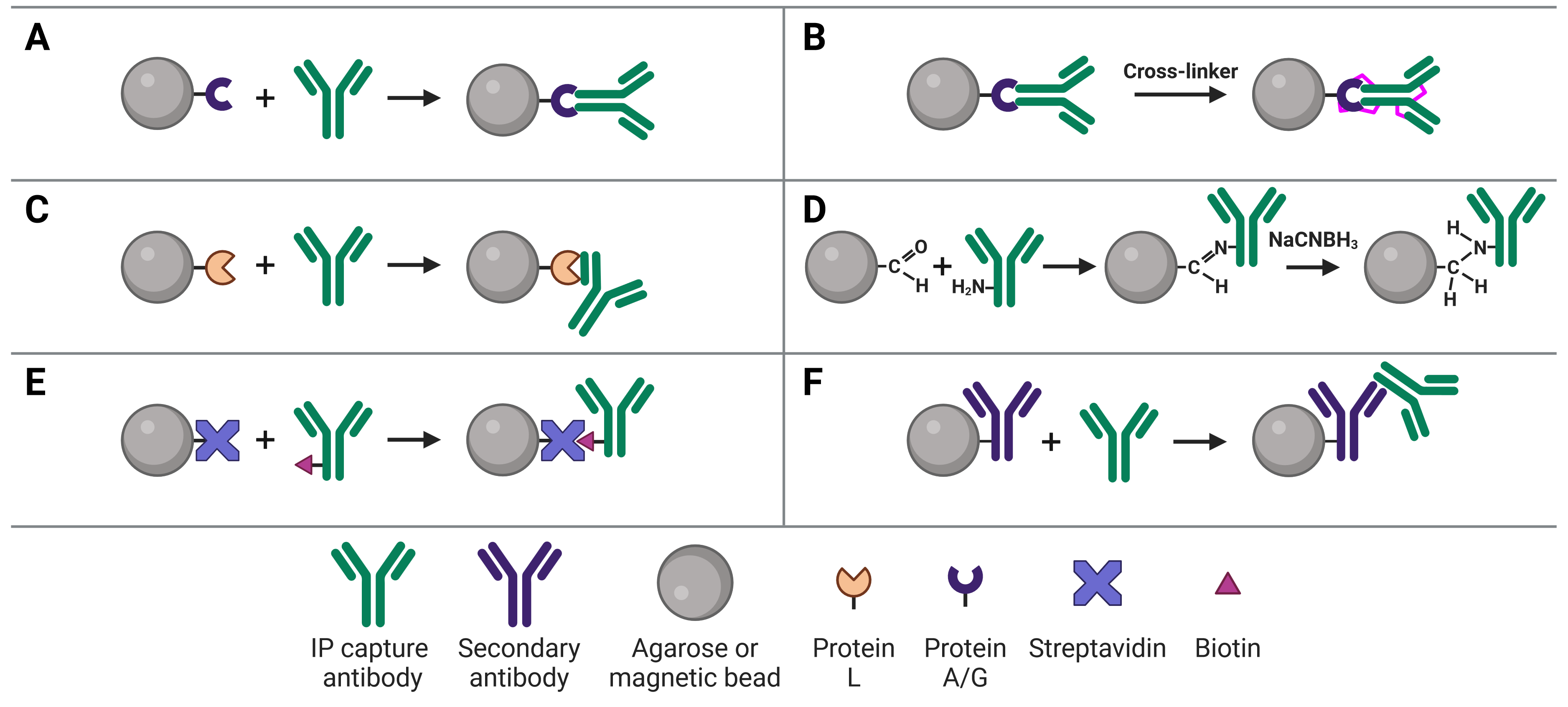

Immobilizing antibodies to the solid phase (beads) is essential for IP, enabling the precipitation of the target protein. While the most common method is to use Protein A or G to capture the IP antibody, various approaches can be used, each of which has its own benefits and applications. These approaches are illustrated in Figure 5 and explained in more detail below.

Figure 5: Approaches to IP antibody immobilization on beads.A, Protein A, G or A/G bind to the Fc region of antibodies. B, Antibodies can be crosslinked to Protein A, G or A/G to prevent eluting the antibodies during antigen elution. C, Protein L binds to the light chain of antibodies. D, Direct immobilization of antibodies to beads obviates the need for Protein A, G or L, and prevents antibody elution. E, Streptavidin-conjugated beads capture biotinylated IP antibodies with very high affinity. F, Secondary antibodies directly bound to beads can be used to capture IP antibodies from a specific host or of a specific isotype, but offer less flexibility than Protein A or G.

Protein A and Protein G

The most common approach to immobilize the antibody to the chosen bead is with Protein A3 or Protein G,4 which are covalently bound to the beads following bead activation with a coupling agent such as cyanogen bromide or N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS). Protein A and Protein G are derived from bacteria, and bind to the heavy chains of the antibody’s Fc region (Figure 5a). Binding to this site has the advantage of orienting the antibody such that the Fab region is clear and directed away from the bead to bind to the target protein.

Due to their promiscuity in generally binding immunoglobulin Fc regions, care must be taken when performing IP on a sample that contains immunoglobulins besides the added capture antibody, such as serum. In this instance, the capture antibody would need to be added to the beads first (pre-immobilized/direct method) and could be covalently bound to Protein A or G (see Covalently Linking Capture Antibodies to Protein A/G below).15

The choice between Protein A and G will depend on the capture antibody’s host species and isotype, because Protein A and G exhibit different binding affinities for different immunoglobulins (Table 5). To circumvent this issue, the recombinant Protein A/G was engineered to contain four Protein A and two Protein G binding sites, and which binds all of the subtypes that Protein A and G bind individually.

| Species | Ig subclass | Protein A binding | Protein G binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | IgA | ++ | X |

| IgD | ++ | X | |

| IgE | ++ | X | |

| IgG1 | ++++ | ++++ | |

| IgG2 | ++++ | ++++ | |

| IgG3 | X | ++++ | |

| IgG4 | ++++ | ++++ | |

| IgM | ++ | X | |

| Mouse | IgG1 | + | ++ |

| IgG2a | ++++ | ++++ | |

| IgG2b | +++ | +++ | |

| IgG3 | ++ | +++ | |

| IgM | +/X | + | |

| Rat | IgG1 | X | + |

| IgG2a | X | ++++ | |

| IgG2b | X | ++ | |

| IgG2c | + | ++ | |

| IgM | +/X | X | |

| Chicken | IgY | X | + |

| Cow | IgG | ++ | ++++ |

| Goat | IgG | +/X | ++ |

| Guinea pig | IgG | ++++ | ++ |

| Hamster | IgG | + | ++ |

| Pig | IgG | +++ | +++ |

| Rabbit | IgG | ++++ | +++ |

| Sheep | IgG | +/X | ++ |

Table 5: Binding affinities of Protein A and Protein G for different immunoglobulins. ++++ refers to strong binding, + is weak binding, X is no binding affinity.

The interaction between antibodies and Protein A/G will occur in most physiological buffers, but binding, and therefore capacity, can be increased by using dedicated Protein A or Protein G binding buffers. Protein A binds IgG best at pH 8.2, whereas protein G binds best at pH 5. However, these buffers may then not be suited for antigen binding, thus optimization of binding buffers is always necessary.

Covalently Linking Capture Antibodies to Protein A/G

Binding of a capture antibody to the solid phase via Protein A/G is not covalent, meaning the antibody will be eluted along with the target antigen at the end of the experiment. If this is followed by a WB, two antibody bands can be visible on the blot at 25 kDa and at 50-55 kDa, corresponding to the light and heavy chains after denaturing. These bands will obscure the signal from the target antigen if the antigen is a similar molecular weight. One method of preventing this (others are discussed in the Analysis section), the IP antibody can be covalently linked to Protein A/G (Figure 5b). Covalent linkage is achieved using a cross-linker such as disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) or bissulfosuccinimidyl suberate (BS3). These are simple carbon spacers with NHS ester groups at either end, which react with primary amines on lysine residues in the proteins to form a covalent link between them.

Protein L

Protein L is derived from Peptostreptococcus magnus and binds to the kappa light chain in the variable domain of antibodies (Figure 5c).16 Protein L is most commonly used with mouse and rat IgM capture antibodies, which bind poorly to Protein A/G. This is due to the heavy chains of IgMs interacting with each other, forming their classic pentameric structure and blocking Protein A/G binding. Protein L is also useful because it does not bind to goat, sheep or cow antibodies, and so can be used for cell culture lysates that contains serum from those species.

Direct Immobilization

Direct immobilization refers to covalent bonding of the antibody to the beads without Protein A, G or L acting as an intermediary (Figure 5d). This is achieved by activating beads with aldehyde groups, which are highly reactive with primary amine groups on antibodies, followed by reduction with sodium cyanoborohydride to form a stable secondary amine bond. This approach can be useful if Protein A/G/L are not compatible with the subclass of IP antibody.

Similarly to covalent bonding of the antibody to a protein support, direct immobilization will prevent the antibody from co-eluting with the target antigen, so it will not be seen on the membrane. As a result, the antibody-bound beads can theoretically be used in multiple experimental runs because the antibody will remain intact and permanently bound. Removing Protein A/G as a component in the system also removes it as a source of non-specific binding during the IP.

The slight disadvantage of this approach is that antibodies are coupled to the bead in a random orientation, as opposed to the directed orientation that results from Protein A/G binding. However, this only has a minor effect on capacity and IP yield.

Other Immobilization Methods

Biotin-avidin binding

Avidin is a protein found in egg whites, while streptavidin is from purified from the bacterium Streptomyces avidinii, but they both have an extremely high and specific affinity for biotin. Biotin is a small 244 Da vitamin that is easy to covalently bond to protein (the carboxyl group in biotin can be modified with reactive groups such as NHS esters, maleimides or hydrazides that target amines (-NH2), sulfhydryls (-SH) or aldehydes (>C=O), respectively, on proteins).

The affinity between biotin and avidin is extremely strong and specific, making it an ideal system for affinity purification, in which a biotinylated antibody is bound by streptavidin-conjugated beads (Figure 5e). Only harsh buffers can dissociate biotin-avidin, such as 8 M guanidine-HCl at pH 1.5, meaning the association will remain throughout all wash steps and not be eluted at the end.

Because any protein can be biotinylated, this system is also adaptable to general pull-downs in which antibodies are not used. The extremely high affinity of biotin-avidin offers a distinct advantage in pull-downs whereby prey proteins can be eluted in a regular elution buffer, but the bait protein will remain attached to the beads. The disadvantage when using biotin-streptavidin for co-IPs is that antibodies are not necessarily oriented in the optimal direction with the Fab region accessible, but this has only a minor effect on co-IP efficiency.

Secondary antibodies

An indirect IP method that is analogous to indirect methods used in IHC, ELISA and WBs uses secondary antibodies directly immobilized to beads (Figure 5f). These secondary antibodies recognize the host species of the IP capture antibody to ensure specificity. For example, a mouse IP antibody could be bound by a goat anti-mouse secondary antibody attached to the beads. The disadvantage of this approach is that it does not offer the flexibility of Protein A/G-conjugated beads, which will bind to an IP antibody from any host.

As illustrated in IP Formats – Individual protein immunoprecipitation (IP), there are two approaches for IPs (Figure 1): the pre-immobilized antibody method in which the antibody is incubated with the bead first, and the free-antibody method in which the antibody is added to the sample lysate first before the beads are added. Using free antibodies can be beneficial in instances where the target protein is low abundance as it can give the highest yield, though it can also give higher background than the pre-immobilized approach. The pre-immobilized method must be used when using direct immobilization approaches, which is highly beneficial in preventing the antibody from being eluted with the antigen, and typically outweighs any minor reduction in yield.

Once the approach has been decided upon, the antibodies are added to the sample lysate and incubated to allow adequate binding. How long this incubation needs to be to ensure sufficient target capture depends on how abundant the antigen is, but anywhere between 1 hour and overnight at 4°C is recommended. Over-incubation, particularly at room temperature, may result in non-specific binding and therefore high background.

After the antibodies and beads have been added, the bead-antibody-antigen complexes are centrifuged into a pellet, allowing the supernatant to be removed. At this point, it is good practice to keep the supernatant until the IP has been verified as successful, in case the majority of the target protein is still contained within.

The beads then need to be washed to remove non-specific binding of other lysate components to the bead, immobilization substrate or antibody. Washing is done using either the original lysis buffer or a dedicated wash buffer, either of which should contain protease and phosphatase inhibitors as the original lysis buffer did. Standard wash buffers consist of PBS or Tris-buffered saline (TBS), which contain physiological levels of salt at a physiological pH, and 0.5-1% of a mild detergent such as NP-40 or Triton X-100. Salt (NaCl) can be increased up to 1 M to increase the stringency of the wash by reducing ionic and electrostatic interactions, while reducing agents (e.g. 1-2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol (BME)) can reduce non-specific interactions mediated by disulfide bridges or nucleophilic attractions.

Elution refers to dissociating the target protein (and often the IP antibody) from the beads to obtain a pure protein sample. While there are some analysis options that beads are compatible with, resolution of protein size by SDS-PAGE and WB is affected by beads. Elution of the protein will also elute the antibody, resulting in bands being present on the subsequent SDS-PAGE and WB, unless the antibody was covalently linked to either Protein A/G or directly to the beads.

Given how prevalent western blotting is following IP, a standard elution buffer is SDS-PAGE sample buffer. This sample buffer is highly denaturing and will therefore easily disrupt affinity-based interactions and prepare the antigen for WB, yet this will not be suitable for all sample types or downstream applications due to its harshness. A more generally applicable, non-denaturing elution buffer is 0.1 M glycine buffer at pH 2.5-3. This can be useful for protein characterization, sequence determination, and crystallization, amongst others. The low pH will cause non-crosslinked Protein A/G-antibody and the antibody-antigen interactions to dissociate, though it is not universally successful and even this can be harsh for some antigens, causing them to denature. Eluting using urea buffer (6-8 M urea, 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl; pH 7.5) is another option, which is particularly useful for downstream MS. Finally, no elution is an option in some cases, keeping the antigen attached to the antibody and beads, because some bioassays and techniques to study protein-protein interactions are unaffected by the presence of the beads.

The proteins purified by IP can be used and studied by a large range of techniques. While the most common are WB and MS (discussed below), protein abundance may be measured by ELISA, function can be determined by various activity assays, and binding and physical characteristics can be studied through biophysical techniques, NMR and crystallization.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot

SDS-PAGE involves first denaturing proteins so that secondary and tertiary structure will not interfere with protein migration on a gel, and then running the denatured protein samples on a gel to determine size and abundance (see our full Western Blot guide). Because the protein solution resulting from IP is relatively pure, simply visualizing all proteins on the gel (which will be primarily the target protein and eluted antibody) by a Coomassie stain after is has run may be sufficient for some experiments. If not, the protein can be transferred from the gel to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane and blotted using an antibody that is specific for the target.

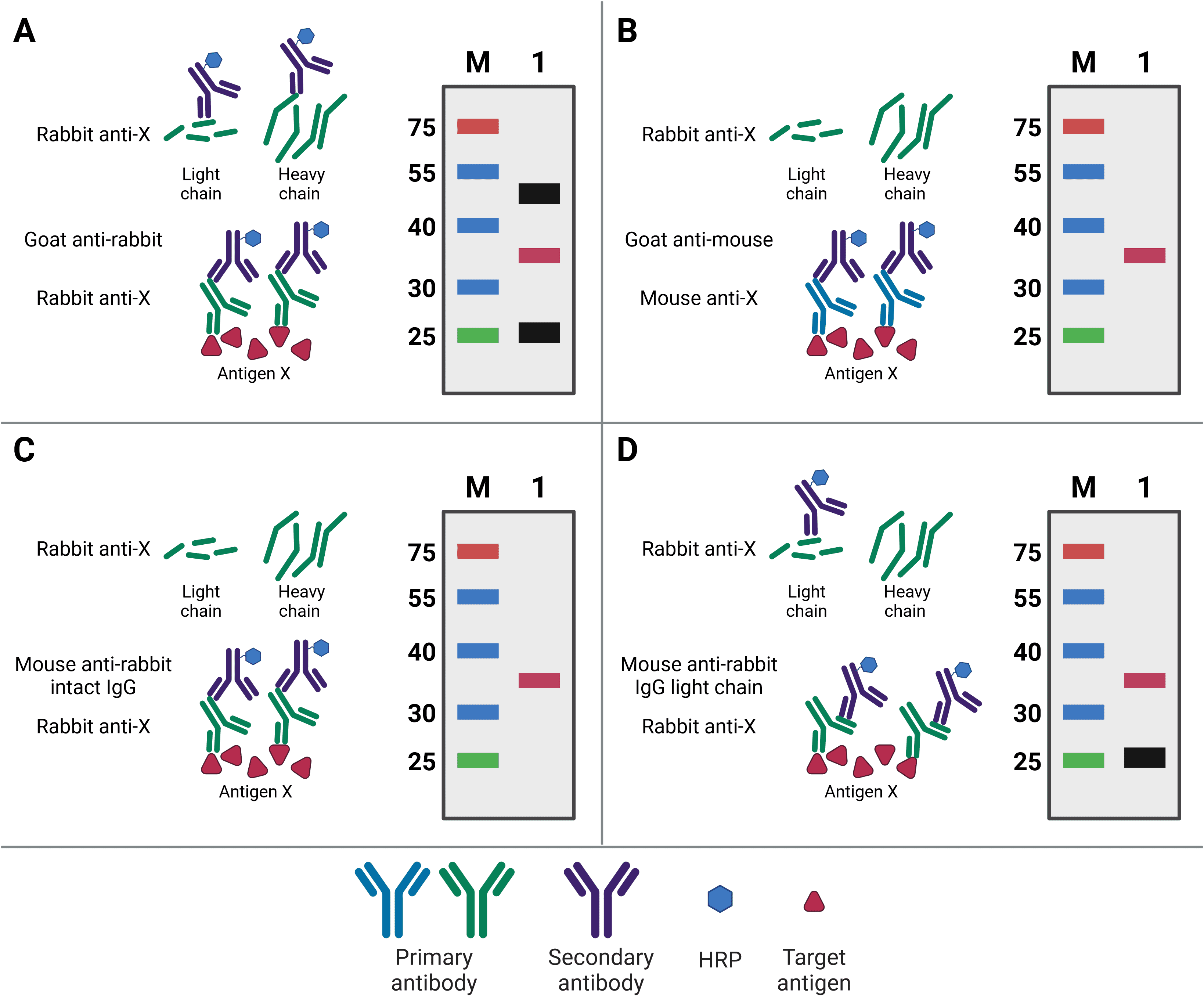

Ideally, the primary antibody used for western blotting will be different to the capture IP antibody. Not only will this increase specificity of the final detection, but it will also prevent detection of any eluted IP antibody. This is because the WB and IP antibodies can then be from different species, meaning the WB secondary antibody will only detect the WB primary antibody (Figure 6). For example, if antigen X is immunoprecipitated by mouse anti-X, but blotted for with rabbit anti-X, then the secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody will only recognize the WB antibody.

Nevertheless, the same antibody can be used for both IP and WB, so long as the target antigen is not the same size as the bands representing the light and heavy chains of the IP antibody after denaturing. These bands are at 25 kDa and 50-55 kDa, respectively, and will obscure the target signal if the target antigen is not sufficiently larger or smaller. Alternatively, covalently linking the antibody directly to the beads or to Protein A/G will prevent its elution and therefore prevent it from being detected on the membrane. A final option is to use secondary antibodies with greater specificity for primary antibody structure. Secondary antibodies are available that only recognize the intact antibody conformation, not the denatured form, or it is possible to use a light-chain-specific secondary antibody. This will recognize the WB primary antibody and only the light chain of the IP antibody, producing a band at 25 kDa but not 50-55 kDa.

Alongside the IP lane, several other samples should be included as important controls. An input lane of 1-10% of the starting lysate material is always included to get a sense of IP efficiency and sensitivity (as described in Sample Types and Preparation). Another indicator of efficiency is to run the supernatant from the IP as a negative control; if the IP was successful and efficient, this lane should be negative. An isotype control, in which the IP is performed with an antibody of the same isotype but that does not recognize the target antigen, is also often included to exclude non-specific binding. For more information on controls, see Immunoprecipitation Controls.

Figure 6: Contaminating antibody bands on western blot after IP. A, Western blot (WB) primary antibody is the same antibody as the (now denatured) IP capture antibody, resulting in the WB secondary antibody recognizing both in the eluate. Bands for the antibody light chain (~25 kDa) and heavy chain (~50 kDa) appear on the WB (black bands) alongside the precipitated antigen (red band). B, WB is performed using a primary antibody raised in a different host (mouse) compared to the IP antibody (rabbit), so the WB secondary does not recognize the denatured IP antibody. No antibody bands appear on the WB. C, WB is performed using a secondary antibody that only recognizes the intact, non-denatured form of the primary antibody. No antibody bands appear on the WB. D, WB is performed using a secondary antibody that only recognizes the light chain of the primary antibody, so the band corresponding to the heavy chain does not appear on the WB.

Mass Spectrometry

MS is an extremely sensitive method of detecting, identifying and quantifying proteins in a sample using peptide sequences resulting from enzymatic digestion of proteins. For MS, proteins are first cleaved into smaller peptide fragments using an enzyme such as trypsin. The peptides are then ionized, accelerated through the mass spectrometer, deflected by a powerful magnet, and ultimately detected.

MS works by measuring the mass/charge ratio (m/z) of molecules, and ionization is necessary so that they are affected by the magnetic field. Heavier ions will be deflected less by the magnet than lighter ions, and ions with a greater charge will be deflected more than ions with less charge. Therefore, the combination of mass and charge determines how strong the magnetic field needs to be in order to deflect the particles to the detector. The abundance of particles with a given m/z is detected and that m/z can then be computationally assigned to a peptide sequence using known sequence information. Using short peptides, rather than intact protein, is important because it increases the chance of being able to assign a given m/z to a peptide sequence. In contrast, a single, large m/z value for an entire protein could represent any number of possible sequences. The disadvantage of this bottom-up approach is that the protein identity must then be computationally reconstructed based on the peptide fragments that are detected, which is achieved using bioinformatics.

MS can provide information about the presence, identity and abundance of proteins, but due to the expensive nature of MS experiments, these parameters for an individual protein IP would more likely be determined using SDS-PAGE and WB. MS after IP is instead most valuable for either determining PTMs (for which WB antibodies may not be available) and for co-IPs, for which it excels at identifying unknown interacting proteins and establishing protein interaction networks. MS can also be used to compare samples in different experimental groups, for example determining if a drug treatment affects a protein’s binding partners, abundance, or PTMs.

Diagrams created with BioRender.com.