By Ryan Hamnett, PhD

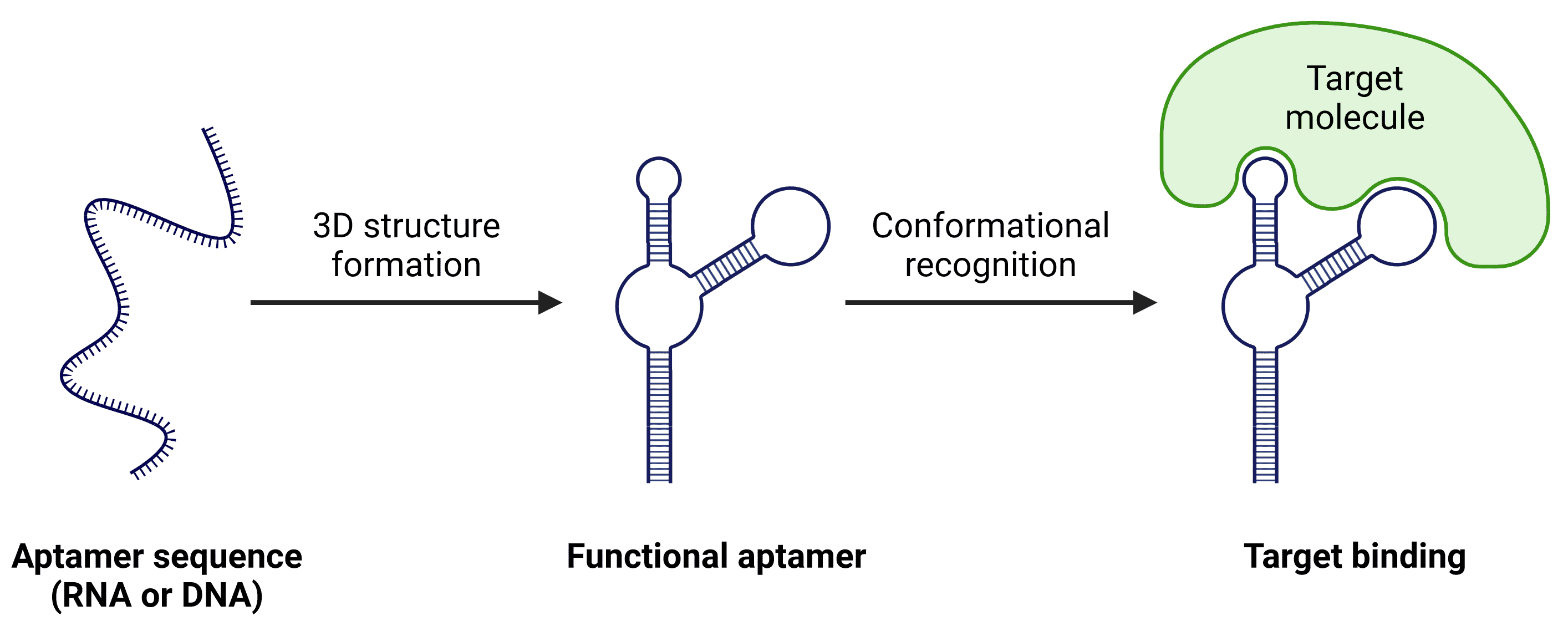

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that fold into specific 3D conformations, allowing them to bind with high specificity and affinity to diverse targets such as proteins, small molecules, and cell types (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Aptamer binding. The precise structural conformation of aptamers allows them to bind to targets with high specificity.

Like antibodies, aptamers are easy to label with reporters, enzymes, or fluorescent tags, making them highly applicable to a wide variety of laboratory and diagnostic techniques, including lateral flow assays, biosensing, and histochemistry. Thanks to their ease of production, cost effectiveness, stability and high specificity, aptamers are gaining traction as versatile alternatives to traditional binding molecules such as antibodies.

We offer aptamers against a wide variety of molecules and cell types, including proteins (e.g. receptors, enzymes), hormones (e.g. insulin), metal ions (e.g. lead), nucleosides and nucleotides (e.g. adenosine), viruses (e.g. influenza), bacteria (e.g. E. coli), and disease-related molecules (e.g. alpha-synuclein oligomers).

Aptamer function is comparable to that of antibodies, binding to specific recognition sites on targets. Similarly to antibodies, aptamers bind with high affinity1 and exhibit high levels of specificity, able to distinguish between proteins that differ by a single amino acid.2 However, aptamers tend to be faster and less expensive to produce, more reproducible between batches (even compared to monoclonal antibodies), and easier to chemically modify.3 Table 1 shows a direct comparison between aptamers and antibodies in a range of key features.

| Aptamers | Antibodies | |

|---|---|---|

| Ease of synthesis | Chemically synthesized | Produced in living systems (animals or cells) |

| Size and structure | Smaller size (~6-30 kDa), better tissue penetration | Larger (~150 kDa) and more complex |

| Temperature stability | -80°C – 100°C | -80°C – 4°C |

| pH stability | Less sensitive to changes in pH, temperature and ionic conditions | More sensitive to environmental conditions |

| Ease of modification | Easily modified or engineered | Modification is more complex and may involve genetic engineering |

| Cost-effectiveness | Generally more cost-effective and scalable | Can be more expensive and time-consuming |

| Specificity | Highly specific | Highly specific |

| Affinity | 10 pM to 10 µM | 10 pM to 10 µM |

| In vivo tolerance | Will not induce immune response. Cleared by renal system without base modification. Degradation by nucleases | Can induce immune response via Fc region. Longer circulating half-life |

Table 1: Key differences between aptamers and antibodies.

Despite the advantages indicated above, aptamers are still considerably behind antibodies with respect to use in research and clinical settings. For therapeutic use, this may be due to the necessity for aptamer modifications to prevent renal clearance and nuclease degradation.4

Use in laboratories may also be limited by nuclease-mediated degradation, particularly for RNA aptamers, whereas DNases are less likely to be an issue in controlled settings. Instead, an early hurdle was a patent protecting the use of SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment), the primary method for developing aptamers that continues to be used today,5 though such patent protection has now expired. SELEX is also labor-intensive, and non-specific background binding during aptamer development significantly affects SELEX efficiency,3,6 but modern innovations in aptamer development are overcoming such issues.7

Finally, as the ‘traditional’ target recognition molecule, antibodies remain at the forefront of biomedical research, with more antibodies currently available for a greater number of target molecules and integrated in research groups’ workflows, despite the plethora of laboratory applications to which aptamers are well-suited.

Thanks to the high affinity, specificity, and available modifications of aptamers, aptamers can replace antibodies in many common laboratory techniques with few adjustments to existing workflows, while making use of the unique advantages afforded by aptamers.

Apta-Histochemistry

Tagging aptamers with fluorophores enables them to be used as direct labels in histochemistry, analogous to direct immunolabeling, removing the potential for secondary antibody cross-reactivity. Histochemical signal amplification remains possible through several methods, including tagging the aptamer with an enzyme such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) instead of a fluorophore, or using biotinylation or enzyme-labelled secondary antibodies directed against the fluorophore on the aptamer.8,9

ELASA

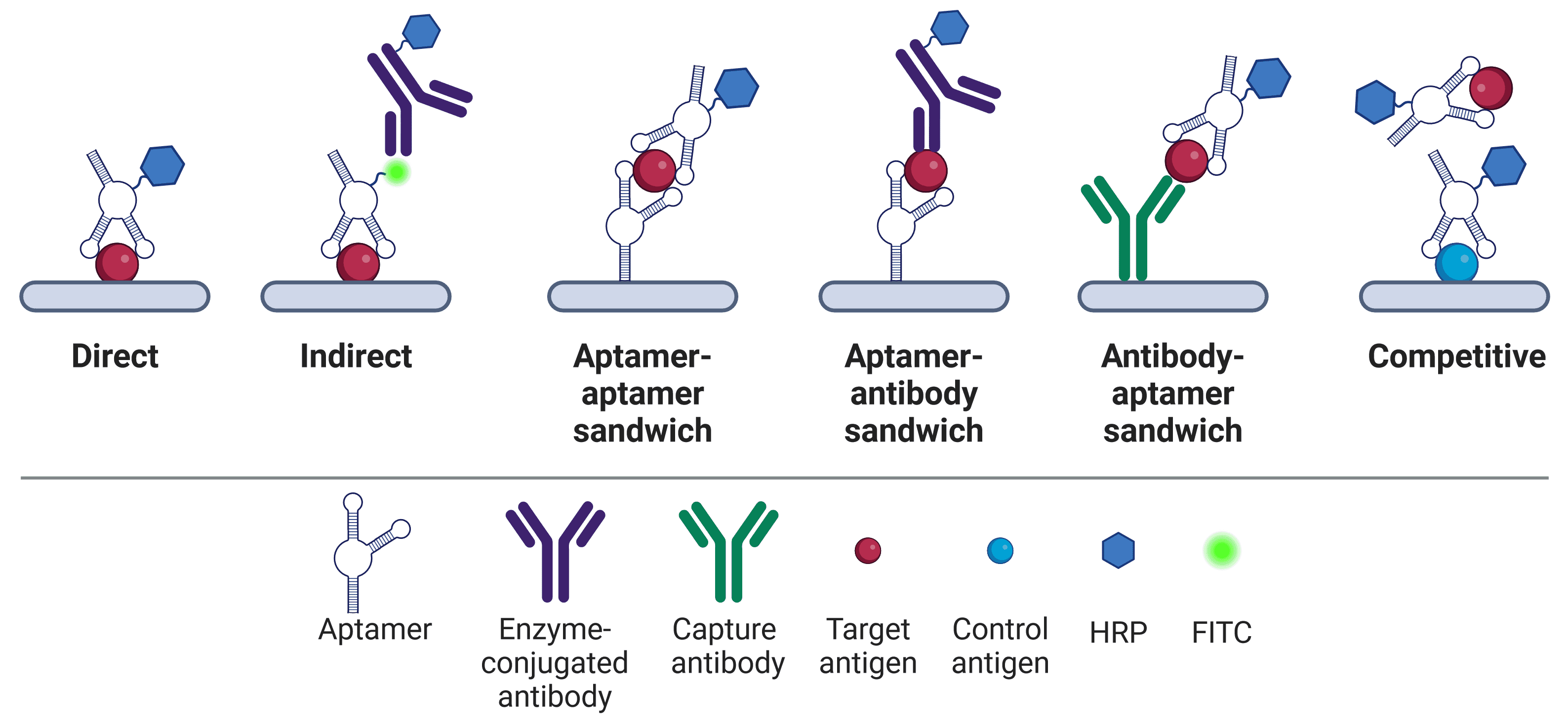

Similar adaptations exist for other biochemical techniques that traditionally rely on antibodies, such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; which becomes enzyme-linked apta-sorbent assay (ELASA)) or western blot.10–14 Like ELISA, ELASA comes in a number of different formats, including direct, indirect, sandwich and competitive (Figure 2). ELASA plates have the potential to be more consistent between batches due to the high reproducibility of aptamers, and ELASA is possible against a wider variety of targets.11 Not only can aptamers be generated more readily for non-immunogenic molecules than antibodies, but aptamers can also recognize environmental pollutants.15 ELASA plates also offer superior reusability potential over ELISA plates, because aptamers can be regenerated.11 Bound antigens can be separated from the aptamer by conditions that would irreparably damage antibodies (heat, acid, salt, proteinase K etc.), but from which aptamers can subsequently refold and be reused.11,16

Figure 2: ELASA formats. Aptamers in ELASAs are used in a similar way to antibodies in traditional ELISA formats. HRP can be directly conjugated to aptamers17 or linked via biotin-streptavidin.18 Not to scale – aptamers (6-30 kDa) are significantly smaller than antibodies (150 kDa).

Affinity Chromatography

Aptamers are particularly useful in affinity chromatography, where their greater stability can withstand harsh elution conditions.19 Alternatively, targets can be eluted via introduction of the complementary reverse strand, changing the conformation of the aptamer and so eluting the target under very mild conditions to preserve target integrity.20 The smaller size of aptamers allows a greater density of aptamers to be immobilized to solid substrates, increasing potential binding capacity, and immobilization of aptamers is easier than antibodies due to aptamers being more amenable to chemical modification.

Apta-Precipitation

The aptamer equivalent of immunoprecipitation, apta-precipitation,21 can be used to precipitate not only proteins, but also small molecules such as adenosine,22 and even cell populations23 in a technique akin to immunopanning.24 Apta-precipitation suffers from fewer contaminants being carried over to downstream mass spectrometry analysis than traditional immunoprecipitation, because off-target binding is more likely to occur on antibodies than aptamers.25

Biosensors use a biological component to detect the presence of an analyte and output a signal proportional to the analyte’s concentration. Biosensors often produce real-time results, tend to be inexpensive, and do not require specialized equipment to operate, making them highly accessible for point-of-care diagnostics and environmental monitoring. The properties of aptamers as recognition elements, including their stability, cost, and chemical versatility, make them strong candidates for biosensors.3,26–28

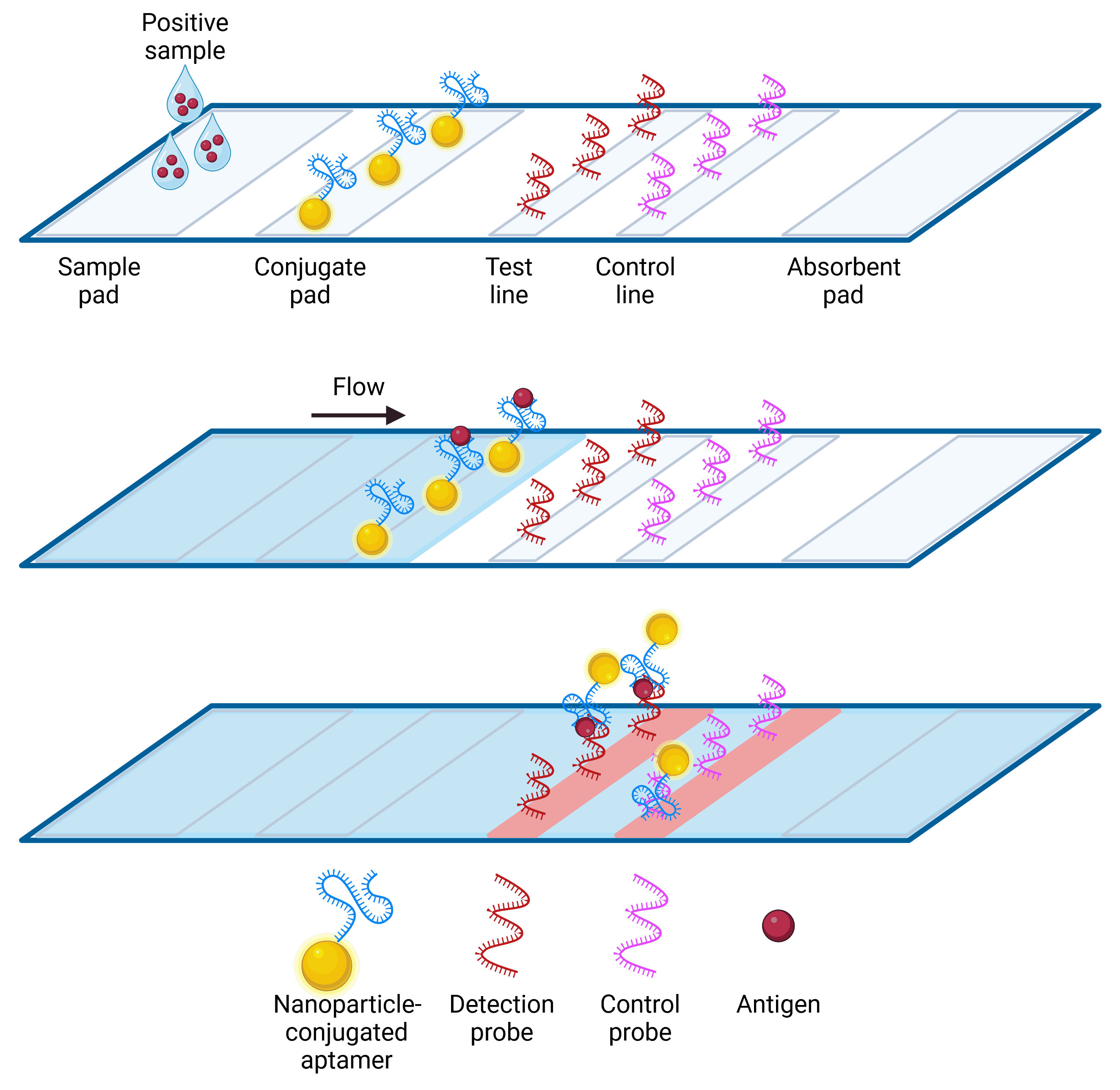

The most common forms of biosensor output come in the form of electrical signal, color, or fluorescence. Colorimetric biosensors in particular are useful in diagnostics, using a color change visible to the naked eye to indicate the presence of a target. The lateral flow assay (LFA) is a well-known colorimetric biosensor, widely used in pregnancy tests and COVID-19 rapid antigen tests. LFAs rely on a sample being transported by capillary action up an absorbent strip, on which it binds to a binding molecule (e.g. antibodies or aptamer) conjugated to nanoparticles. A visible colored line appears at the site of nanoparticle accumulation at the positive test line and/or the control line, with accumulation occurring due to the presence of additional binding molecules at those sites (Figure 3). Chemical modification of aptamers makes them easier to conjugate to nanoparticles with a consistent orientation than antibodies, and they also have a longer shelf-life at room temperature.

Figure 3: Lateral Flow Assay using aptamers. Sample containing analyte is dropped onto the sample pad, and then flows by capillary action. Analyte specifically binds to the nanoparticle-conjugated aptamer, which is then carried to the test and control lines. Nanoparticles bound to analyte are captured by the detection probe and accumulate at the test line, while excess nanoparticle-aptamer conjugates carry on to the control probe to confirm the test is working. The control probe may be streptavidin, to capture a biotinylated aptamer, or it may be a complementary oligomer.29 Accumulation of gold nanoparticles produce visible red or blue lines depending on nanoparticle size.30

Aptamers have the potential for extensive use in clinical settings, with the first therapeutic aptamer, pegaptanib (Macugen), approved by the US FDA in 2004.31 Aptamers are able to bind target molecules and deliver therapeutic compounds with similar alacrity to antibodies, while being cheaper to produce and maintain. This makes them particularly attractive for point of care testing,32 but they have also found applications in diagnostics,33,34 drug discovery,4,35 and treatment.36

Aptamers are traditionally developed by SELEX, which was conceived in 199037 and continues to be used today, although new methods are being developed to overcome issues with SELEX, such as being labor-intensive and sometimes failing to produce aptamers of sufficiently high selectivity.7 SELEX involves repeated rounds of exposing an oligonucleotide library (the putative aptamers) to the target, identifying and isolating the oligonucleotides with the strongest target binding properties, amplifying the selected nucleotides, and repeating the process under more stringent conditions (Figure 4). This cycle is usually repeated 10-20 times until an aptamer of sufficient affinity and selectivity is found.

Figure 4: SELEX process for producing aptamers.

Aptamers are usually made of single stranded DNA or RNA, though non-natural nucleic acids and mirrored enantiomers (L-DNA or L-RNA) have also been used, increasing aptamer diversity and stability, respectively.3 While no differences have been observed between DNA and RNA in terms of specificity or affinity, DNA tends to be more stable, cheaper, and does not require reverse transcription, while RNA is more flexible and so can fold into a greater number of potential structures.11 Most recently discovered and applied aptamers are DNA-based.3

A library of 1014–1015 unique, random aptamers is used as a starting library. Each aptamer contains a random region for binding, flanked by two constant 5’ and 3’ regions for PCR amplification and, in some cases, structure. The length of each aptamer varies between experiments, but random regions are typically 36-70 nt long.3,38 RNA libraries are generated by in vitro transcription of DNA templates, while DNA libraries must be prepared by strand separation of double stranded PCR products.4

Once generated, the sequences are exposed to the target (protein, metal ion, small molecule etc.), which has often been immobilized to a solid substrate such as a bead for manipulation.39 Aptamers that bind successfully are retained by the bead-bound target, while non-binding aptamers are washed away. The bound sequences are eluted away from the target and amplified by PCR to create another library. Subsequent rounds of selection are performed under different stringency conditions to ultimately identify sequences with the strongest binding properties.39

We offer over 400 biotinylated DNA aptamer products for research use in a wide variety of applications. Below we have listed some of our most popular aptamers.

| Aptamer | Target Type | Aptamer Chemistry | Conjugate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Tryptophan Aptamer | Amino Acid | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Kanamycin Aptamer | Antibiotic | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Aptamer [S6] | Cells | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Staphylococcus aureus Aptamer [SA20] | Cells | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-IL-6 Aptamer | Cytokine | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Fentanyl Aptamer [F6] | Drug | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Rituximab Aptamer [C10] | Drug | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Estrogen Aptamer [BES.1] | Hormone | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Insulin Aptamer [IBA] | Hormone | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Lead II Aptamer | Metal ion | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-ATP Aptamer | Nucleoside Triphosphate | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-alpha Synuclein Aptamer | Protein | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Glucagon Receptor Aptamer [GR-3] | Protein | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Histone H4 N-Terminus Aptamer [4.33] | Protein | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-HIV1 Reverse Transcriptase Aptamer [PF1] | Protein | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-His Tag Aptamer [6H7] | Protein Tag | DNA | Biotin |

| Anti-Clostridium Difficile Toxin B Aptamer | Toxin | DNA | Biotin |

Diagrams created with BioRender.com.